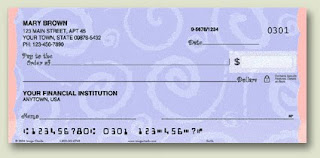

Ever since I was a kid, I have been baffled by the concept of check writing. Essentially, when you write a check, you're saying to someone, "I have the money I owe you, but it's not with me right now. I'll write you this note that says how much money I'm giving you and if you take it to my bank they'll give you the money."

Ever since I was a kid, I have been baffled by the concept of check writing. Essentially, when you write a check, you're saying to someone, "I have the money I owe you, but it's not with me right now. I'll write you this note that says how much money I'm giving you and if you take it to my bank they'll give you the money."This primitive system is totally based on trust. If the person writing you a check has made a mistake in their checkbook or if they are simply lying to you about the document's validity, you may not ever get paid.

A bad check will cost you money in fees from your bank and will likely cause you to unknowingly issue a few bad checks of your own. Maybe the person writing a check to you has received a bad check and will be surprised that they never paid you.

One bad check can start a chain reaction through the accounts of any number of people, bringing headaches for people who don't deserve them and a money train of fees collected by their banks.

When everything goes right - if someone writes you a check that actually is good - it can take as long as a week before you are able to spend the money. That's because when you deposit a check into your account, your bank has to then send it to the issuer's bank to actually collect the money for you before the funds are available to spend. This delay of typically 3 to 5 days is a hassle as well.

When everything goes right - if someone writes you a check that actually is good - it can take as long as a week before you are able to spend the money. That's because when you deposit a check into your account, your bank has to then send it to the issuer's bank to actually collect the money for you before the funds are available to spend. This delay of typically 3 to 5 days is a hassle as well.There's a reason "the check is in the mail" is a funny line. It takes forever to move money this way. Convenient, because usually the person saying it hasn't mailed it yet.

This isn't the first time I've written of the absurdity of this system and the ways American banks exploit it to collection hundreds of millions of dollars each year by generating a laundry list of stealth fees on their customers' accounts.

One of the most popular things I've written over the years was an article titled In Banker's Clothing. By "popular" I mean that I hear about it from people more than most other things I've written. Maybe it's not so much popular as it is something that invites them to share their feelings of mutual disgust and infuriation. Like health care, every American has a banking horror story.

One of the most popular things I've written over the years was an article titled In Banker's Clothing. By "popular" I mean that I hear about it from people more than most other things I've written. Maybe it's not so much popular as it is something that invites them to share their feelings of mutual disgust and infuriation. Like health care, every American has a banking horror story.In 2001, I bounced a check when registering my car in Louisville. This was right before I moved to Rhode Island. The news of a bounced check is communicated by mail, which takes a long time, especially when there is an out-of-state change-of-address involved. I really can't express what a series of pains in the ass the chain reaction of this bounced check became.

Even though I repaid the check to the office as soon as I found out about it, unbeknownst to me, the County Clerk's office issues arrest warrants for these infractions. Furthermore, such a warrant is not automatically canceled upon payment.

Years later during a visit to Louisville, I was arrested and spent the night in jail - not for jumping the fence of an apartment building with a bunch of friends to go swimming in the middle of a hot night, but for a bad check that I had repaid years ago and forgotten about.

I'm no fan of banks, suffice it to say. For years, my life has been conducted as much as possible in a cash-only manner. I do have a bank account and debit card, but I have not had a credit card or any loans or real debts in more than ten years.

Funny thing, if you jump out of the system like I did, it's almost impossible to get back in. A few years ago I tried to buy a house in Louisville. I have been a lifelong renter and this was at the time when "everyone can buy a house" in America. Well, not me. I had more than one mortgage specialist tell me, "You don't have a credit score. I've never seen anything like it." In the '90s, I had bad credit, now I have none. Possibly it was a blessing in disguise that I was unable to buy a house when "everyone" could. We all know how that turned out for "everyone."

When I started writing this article today, I had a line in it that described checking as "a preposterous, archaic, 18th Century way to do business." Upon further research, I found I was being way too generous with that burn. In reality, checking dates back to the 3rd Century. Yes, the Third Century. You know, about 1,800 years ago? The fucking Romans came up with it! One empire's innovation is another empire's... I don't know, something.

In the same way that personal checks rely on everyday people to be both honest and skilled in math, so do income taxes. It is truly mind-boggling that individual Americans are responsible for calculating their own taxes each year.

In the United States, the country that is the undisputed world capital of inventing new ways to scam people, expecting everyone to honestly calculate their own share of taxes is simply an insane way to collect funds for public services.

Not too long ago, The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that "an estimated 30 percent to 40 percent of taxpayers cheat on their returns, defrauding the government of some $290 billion a year, according to an Internal Revenue Service analysis of 2001 returns. Some believe the real percentage of tax cheats is much higher."

Not too long ago, The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that "an estimated 30 percent to 40 percent of taxpayers cheat on their returns, defrauding the government of some $290 billion a year, according to an Internal Revenue Service analysis of 2001 returns. Some believe the real percentage of tax cheats is much higher."How much money is $290 billion a year? Quite simply, it is more than almost any previous year's Federal Budget Deficit. (Read that again!)

The Federal Deficit is an annual number that is the difference between what the government collects and what it spends. Each year, this difference is added to the national debt.

Before this year's stimulus-reinvestment-bailout budget, the annual deficit had only tickled $290 billion a few times. The amount of money that individual Americans are defrauding their own government is a main reason why the nation is in debt. It averages out to about $2,000 per taxpayer per year.

Theoretically, if Americans were not cheating on their taxes, the government would never have needed to borrow money from banks or foreign nations, and consequently would not be in debt.

You could, of course, go further and say if the US was not fighting two simultaneously monstrous wars that are draining the coffers, the resulting surplus and ability to provide better services would be even more spectacular. And if you wanted to, you could argue that if Americans weren't already paying one of the lowest tax rates in the industrialized world, and if everyone over a certain income level (including corporations and religious groups) paid taxes at a fair, across-the-board rate... well, I was dreaming when I started this line of thought in the first place.

Only about 1% of tax returns are ever audited. Those are pretty good odds and Americans know it. Joe Antenucci, professor of accounting and finance at Youngstown State University said, "Any gambler will tell you, when you have a high payoff and low risks, that is when you want to be involved."

Just like with check writing, when everything goes right, taxes are also a headache. Each year, Americans labor through confusing tax forms, calculate their taxes, and live in fear of the IRS. A national poll conducted by the Discovery Channel in 2000 showed that 57% of Americans feared the IRS more than God.

Just like with check writing, when everything goes right, taxes are also a headache. Each year, Americans labor through confusing tax forms, calculate their taxes, and live in fear of the IRS. A national poll conducted by the Discovery Channel in 2000 showed that 57% of Americans feared the IRS more than God.Nothing's scarier than getting an envelope in the mail with their logo on it, even if that logo looks like a chicken with big tits.

How does this have anything to do with my ongoing discovery of Swedish culture?

Rightfully so, both check writing and self-calculation of your own taxes seem totally insane to Swedes. As you might have guessed, the back-asswards process of individuals calculating their own taxes and being responsible for the errors is uniquely American. It's almost as insane as trusting someone who writes down an amount of money on a piece of paper, thereby magically transforming that piece of paper into a bank note worth that amount.

In Sweden writing a check to make a purchase or pay a debt is something that happens only at very high levels of corporate trade and finance. Ordinary people never come in contact with checks.

Instead of personal checks, in Sweden (and in essentially every European country), they use a system called giro (or girot, depending on the country, all pronounced JEE-roh). The nearest thing Americans could equate it with is direct deposit. However, the difference between giro and direct deposit is that giro goes in both directions. It is not just for deposits and the system is accessible to individuals, not just large companies.

For example, if you get a bill in the mail for your rent, telephone service, cable TV, school tuition, or anything else, it comes with a tear-off stub that has a unique giro number on it. You take the stub to your bank and give it to the teller. The money is instantly transferred from your account to the requester's account. No waiting. Because of the unique number assigned to each stub, the company instantly knows you have paid them. Of course, this can all be done online as well, and some of these debits happen on regularly scheduled dates, requiring you to do nothing.

For example, if you get a bill in the mail for your rent, telephone service, cable TV, school tuition, or anything else, it comes with a tear-off stub that has a unique giro number on it. You take the stub to your bank and give it to the teller. The money is instantly transferred from your account to the requester's account. No waiting. Because of the unique number assigned to each stub, the company instantly knows you have paid them. Of course, this can all be done online as well, and some of these debits happen on regularly scheduled dates, requiring you to do nothing.Wow, this giro system that processes instant payments from account to account sounds pretty modern, right? It must be on the cutting edge and reliant on fairly new technology. Guess again. Sweden implemented the giro system in 1925. By the 1950's, practically all of Europe was using some variant of it. For decades, it has been the standard way money moves in Europe.

Sveriges Riksbank, which is Sweden's central bank, says that in 2007, "giro transfers accounted for a good 94 percent of the total value of transactions and for 29 percent of the number of transactions" in the country. Most small transactions are completed with debit and credit cards, and by "most" I mean practically all of them. Riksbank says it was 62% of all transactions in 2007. Paper money was barely a blip on the radar (which is a shame since Sweden's currency is downright gorgeous) and checks were basically non-existent.

In fact, several of my Swedish friends have told me they have never seen a check in real life. They know what checks are only from American films and television. You'd think it would be funny, like when you see an 8-track tape in an old movie. To the contrary, even in Sweden, a country intimately familiar with American culture, someone writing a check is one thing that seems truly foreign.

Swedes use debit cards for everything. Even the tiniest, little amounts, like one cup of coffee or a candy bar at a convenience store are paid for with cards. Almost nobody will run a tab at a bar - each individual drink is paid for with an individual debit card purchase each time - and most of these transactions require a PIN code entry at the point of purchase.

Swedes use debit cards for everything. Even the tiniest, little amounts, like one cup of coffee or a candy bar at a convenience store are paid for with cards. Almost nobody will run a tab at a bar - each individual drink is paid for with an individual debit card purchase each time - and most of these transactions require a PIN code entry at the point of purchase.A few months ago, while I was in Sweden, someone made a duplicate of my debit card and went on a shopping spree in Florida. Sophisticated thieves are apparently now able to manufacture fake cards with real numbers and use them in stores. Someone's card number can be intercepted virtually anywhere and a new card can be produced from it. This was the second time it has happened to me.

Every Swedish person I talked with about the situation asked the same question, which was not "How did they get your card number?" but rather, "How did they get your PIN code?" Swedes are blown away by the fact that you don't need a PIN code to make a purchase with a card in America, all you need is the card. And if you're making a fake card, you can just put a name on it that matches an ID you have, on the off chance that a merchant asks for your ID.

Checks, giros, debits and taxes all cross paths at this point in our discussion. In Sweden people are paid from their jobs in essentially the same automatic way as they pay their bills. On the 25th day of every month, money appears in their accounts automatically. (Good luck going out to eat or to the state-run liquor store Systembolaget on the Friday after the 25th.)

Money appearing in your bank account is like direct deposit in America, and this happens with the taxes already deducted, but that's where the similarity ends as far as taxes are concerned. For Americans, the amount removed from their paycheck is just one piece of a nerve-wracking puzzle that must be assembled in paperwork at the end of the year.

Money appearing in your bank account is like direct deposit in America, and this happens with the taxes already deducted, but that's where the similarity ends as far as taxes are concerned. For Americans, the amount removed from their paycheck is just one piece of a nerve-wracking puzzle that must be assembled in paperwork at the end of the year.For the majority of Swedes, everything about tax collection is also automatic. Taxes are taken out of your wages before they are deposited into your bank account. At the end of the year when your tax forms come in the mail, all the numbers are already filled in. That is, when you open the envelope, all the numbers are already on the page. All you have to do is confirm that the numbers are correct, which you can do by telephone, text message, or computer. If everything looks right, that's all you have to do. You're finished. (There's more to it if you're self-employed or a business owner, of course.)

You're not faced with a stack of confusing forms or the burden of fear if you make a mistake.

I should mention something else as well, that Swedish tax forms are comparatively beautiful. They're borderline cute even (this year's forms had a flower and a cartoon kitty cat on the front), colorful, reminiscent of Ikea order forms and easy on the eyes. The tax collection agency, Skatteverket, even has a logo that's not so bad either.

Aside from automatic income taxes and the 25% sales tax, as I discussed a few months ago, there is one tax in Sweden that people are expected to pay voluntarily. That is the television and radio tax. This tax of about $250 a year helps regulate the airwaves and backs the operation of five publicly-funded television networks and more than forty streams of radio programming.

Aside from automatic income taxes and the 25% sales tax, as I discussed a few months ago, there is one tax in Sweden that people are expected to pay voluntarily. That is the television and radio tax. This tax of about $250 a year helps regulate the airwaves and backs the operation of five publicly-funded television networks and more than forty streams of radio programming.Whereas 40% of Americans are cheating on their income taxes, even though many Swedes hate the TV and radio tax and feel it is unfairly levied, 9 out of every 10 Swedes are sending in these additional payments voluntarily. Only about 10% are not.

Long story short, for every American who has cried "there's got to be a better way" when balancing their checkbook or preparing their income taxes, well, there are better ways. Again, just like health care, these better ways haven't been made available to Americans, probably because there are people somewhere making tons of money off of keeping the systems broken and confusing.

It's only common sense that there should be no delays, doubts or leaps of faith necessary in financial transactions or tax collection.

Both of these complex, antiquated systems invite inaccuracies and unnecessarily allow the processes to become corrupted. Americans can't be relied on to do the right thing if the opportunity to make an extra buck exists.

Further, in a country whose schools are so lacking, I'm not sure who ever thought it would be a good idea to trust the general public with math. We need not mention the complexity or comprehension involved in addition to the calculations required for paper-based banking and tax preparation.

Even though I had the advantage of being able to go to private schools in my youth, I was never in a course that covered balancing a checkbook, preparing tax forms, calculating annual percentage rates, or any of the basic, real-world financial knowledge every last dumb ass is expected to have.

No wonder 57% of Americans are more afraid of the tax man than the wrath of God. A simple mistake can put you in jail, and if you don't understand how it's supposed to be done in the first place, well, that starts you off with a pretty wide margin for error.

I know Obama's got a lot on his plate and neither of these topics will likely ever be addressed, given the larger, pressing issues of the moment, but like those problems, I think these are indicative of a pervasive "if it ain't broke don't fix it" mentality. Such thinking can only ultimately result in nothing ever being improved, until it reaches the point of being unwieldy.

It is possible to fix things that "ain't broke." In fact, it's advisable. If people made something, there's always room for improvement. You can't just keep adding rooms on to the outhouse until there's a ramshackle mansion attached to it.

The check system, I think it took me about 3-4 checks until I got how I was supposed to do.. =P

ReplyDeleteBut I didn't like it when it took 3 days until the money got on my acount when I needed it the same day to pay for school and I couldn't cash the wole check either.. =P

I think it is really fun too read everything form your perspective!